Architecture, at its very best, is a marker of space: a careful reinvention of a piece of land, inviting play and possibility. At its worst, however, it becomes a delineation of social order, a symbol of power and a threshold of who’s in and who’s out.

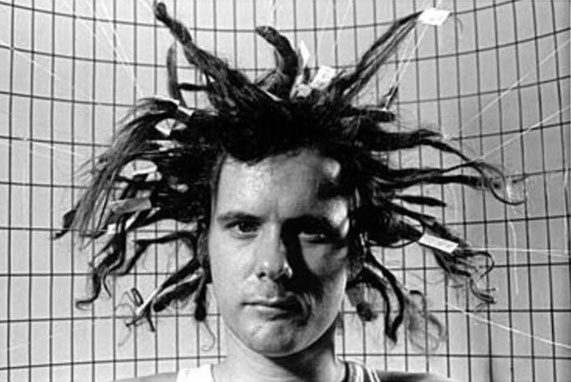

It’s precisely this notion of privacy, a separation from the public, the humane and the universal, that Gordon Matta-Clark explored through his lifetime as an artist and self-titled anarchitect. Trained as an architect in the 60s, at the Cornell University College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, a time ripe with post-war modernist trends in architecture in design, Gordon found myself questioning his role as a designer and instead turned to the arts to explore and express his critique of the the contemporary architectural zeitgeist, particularly the world-building ideologies of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus Movement.

To that end, his work demonstrates how the language of modernism (and that of its colder cousin Brutalism) loses its meaning in the rigid materialism it evangelises. After all, modernist architecture was a utilitarian endeavour and served to rebuild the world after the horrendous destruction caused by the World Wars. But over time, it took an industrial function, producing and reproducing modular spaces that — in Gordon’s mind — lacked a touch of the non-material essentialism that lies at the heart of the human experience. It’s precisely this cold concrete philosophy, devoid of any emotion or feeling, that Gordon was so strongly opposed to and attempted to communicate with a lifetime of work.

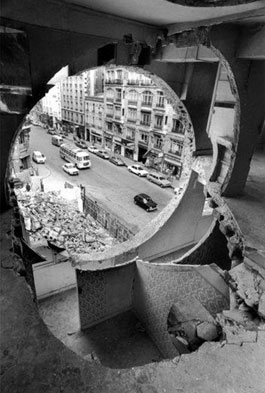

His body of work demonstrated the discursive wrestling match he was fighting with architecture, even going so far as to literally tear a building through the middle to demonstrate how specific architectural designs construe specific realities, potentially utopic to some but also deeply oppressive to so many others. It’s here, in his 1974 collaborative project Anarchitecture, that we witness the thesis at the heart of his argument: that modernism was no longer in alignment with modern times, that it’s deep philosophies only embedded the exclusive ideologies of the rich and powerful. He was modernism’s principal critique and, in many ways, a pioneer of the postmodernist movement; one that sought to remarry aestheticism and expressionism to modernism’s functional outlook.

Personally, I see his work as an exploration of the in-betweens; he was an individual brave enough to study the gaps between disciplines, locating meaning in the infinite and creating space for evermore. As an architect himself, he went a step ahead of the designer-client relationship to locate the folly at the heart of the design: the meaningless, the unnecessary, the benign; seeking to shed light on those very raw materials that could one day define new meaning. After all, isn’t that the special (and spatial) role of the anarchitect? To dismiss the system as it stands, to create space — even if just for a moment — for something new.

Text by Kaira Puri

Image Courtesy: Carol Goodden, Canadian Centre for Architecture, and Art Institute Chicago

Find out more about the Artist and Gallery:

http://www.artnet.com/artists/gordon-matta-clark/

https://www.moma.org/artists/6636