How India Melted the Frieze [With Warmth and Wonder] – Indian Artists at Frieze, London, UK

Looking at Mrinalini Mukherjee’s massive hemp installations at Tate Modern last year, I wondered if the world was getting enough of these; and so it was hardly surprising when I learned that her work at Frieze London last week was quite the hot property—one of these was reportedly sold even before the fair opened, and another was reserved for an institution within just a few days.

If there was one Indian artist that commanded great interest at the fair then it would be Mukherjee, without question. But there was not just one. The other Indian artists that left an impression with their diverse and distinct works at the Regent’s Park spectacle included Himali Singh Soin, with her 2019 Frieze Artist Award commission; Hemali Bhuta; Neha Choksi; Raqs Media Collective; Sandeep Mukherjee; and Sarnath Banerjee.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Woven, 1996-2013

(Image Courtesy: Nicola Marittu / Nature Morte, New Delhi)

At the hugely popular Booth W05, gallery Nature Morte participated in the Focus section, featuring a solo presentation of works by Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949-2015). Titled Woven, this section was curated by Cosmin Costinas, executive director and curator at Para Site in Hong Kong. The sculpture was created from three very different materials – fiber, ceramic, and bronze – but her language was consistent in all three, even while working with their radically different properties, exploring the formal parameters of the figurative, vegetal, and the abstract.

Nature Morte presented four sculptures by the artist, starting with a work in fiber from 1996 and three works in bronze made in 2013 from the final period of her career (reportedly priced between $60,000 and $170,000). Following her experiments with fiber and ceramics, Mukherjee approached bronze as a malleable material, casting both wax elements that the artist created and found objects from nature, combining them into welded assemblages. Her bronzes appeared kinetic, molten and primordial, and radically expressive.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Woven, 1996-2013

(Image Courtesy: Nicola Marittu / Nature Morte, New Delhi)

“We received a phenomenal response to Mrinalini Mukherjee’s works at the Frieze London art fair this past week. We were only able to show one fiber work and three bronze works, but people were enthusiastic to see them. It seems that many people had seen the retrospective exhibition at the Met Breuer in New York and even those who were not able to see it in person were aware of it. The works speak to a universal aesthetic and are certainly in no way limited to an Indian audience,” says Peter Nagy, founder of Nature Morte.

Also part of the Woven narratives, in which Mukherjee’s work appeared, was a presentation by artist Chitra Ganesh who was represented by San Francisco based Gallery Wendi Norris. “I am interested in considering the garden as a site at the intersection between creation and destruction,” she said while introducing her installation, Unearthly Delights. Mumbai-based artist Monika Correa, who was represented by Jhaveri Contemporary and presented black-and-white tapestries made primarily with unbleached cotton and wool, furthered the narrative of Indian textile at the fair. Correa devised techniques that challenged the methodology of weaving itself, with works such as the Dudhsagar Falls, inspired by a four-tiered waterfall in the artist’s home state of Goa. Here, Correa distils weaving into pure form, as freely meandering threads come to form their own patterns.

But classic wasn’t the only statement that India made at Frieze. Himali Singh Soin, who lives between London and New Delhi, raised some relevant questions about climate change and history with her 12-minute multimedia presentation on video. Titled We Are Opposite Like That, the commission as part of the 2019 Frieze Artist Award explored the ecological impact of human habit through fictional storytelling. Soin, from her travels to the Arctic region, used the metaphor of melting fossil — ice — that has witnessed historic changes throughout time, and dwelled on the Victorian fear of the ice age much like our own anxiety from an impending natural catastrophe ahead.

Another interesting piece of performance was that by Yasmin Jahan Nupur. Her interactive, informal and insightful Tea Parties with conversations on history, travels and the origins of the leaf itself provided a good break to many an over-walked visitor at the fair. “A gentle and generous artist with a passion,” read a testimony by Juliette Bijoux.

The maharajas weren’t far behind. Prahlad Bubbar reimagined the grandeur of the life of Maharaja Yashwant Rao Holkar II with his exhibit, Modernist and Art Deco Paradise: Indore, a collateral to his Paris exhibit, Modern Maharajah. The Maharaja’s Manik Bagh was built with regal American walnut, sycamore, alpaca silver, faux leather, white frosted glass and everything that was as exquisite as the good old times of the crown.

At Booth G25, the narratives were starkly different. The Project 88 booth displayed artworks that employed material processes and narrative techniques to address notions of space and time from historiographical as well as socio-cultural standpoints. Through abstract gestures and specific references, the works permitted notions of chance and speculation to aid imaginative and conceptual considerations.

Hemali Bhuta, Blank for a Blank, 2017

(Image Courtesy: Hemali Bhuta / Project 88)

Mumbai-born Hemali Bhuta’s Subarnarekha works, for instance, employed gold in reference to a geographical area rich in the resource and also used its geological nature to divulge the absurdity of political borders that have had grave consequences in the same region.

Neha Choksi, Missing Monument – II, 2014

(Image Courtesy: Neha Choksi / Project 88)

Neha Choksi, who once told me that she sees her practice as a “tendency to disrupt the accepted” whether by performance or other media, presented four small bronze sculptures, each titled Missing Monument. In this series, the artist gathered the elements of the lost-wax process of making bronze sculptures into self-referential totems of the methodology. The Cup, Sprue, Gate, and Vent are the parts of the production usually removed in fashioning the final sculpture. Here these very elements came together in a series of modest ensembles suggestive of the missing monuments they might have brought into being.

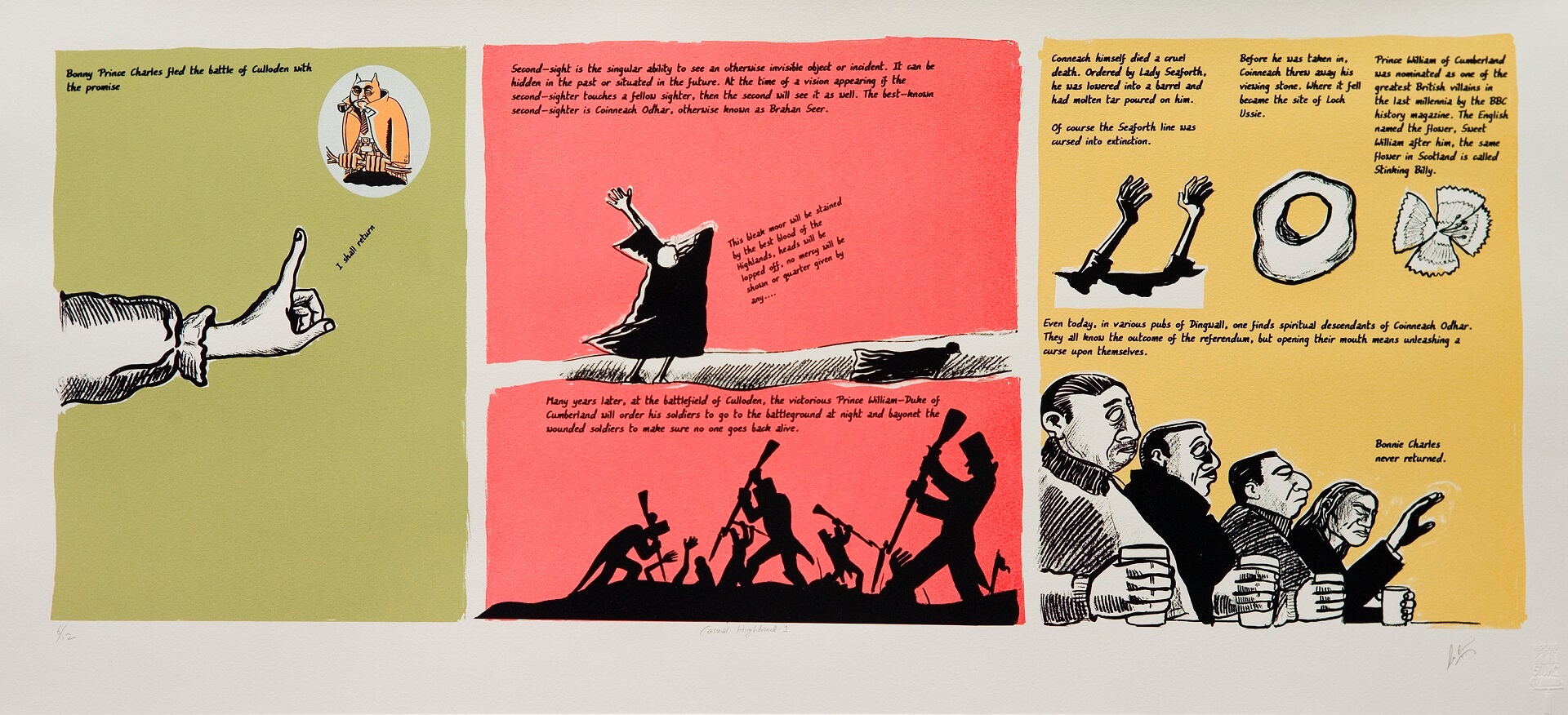

Sarnath Banerjee, Casual Highland I, 2014

(Image Courtesy: Sarnath Banerjee / Project 88)

At the same booth, graphic storyteller Sarnath Banerjee’s screen prints, Casual Highland I, II, fused fact and fiction to generate new stories about the Scottish Highlands, which he walked on his own for many nights while working with the Highland Print Studios in Inverness. It was idiosyncrasy and myth over dispassionate truths to challenge existing historical narratives about the “the edge of civilisation” as he experienced it by way of chilling landscapes, chatting with locals and collecting folklore and memories.

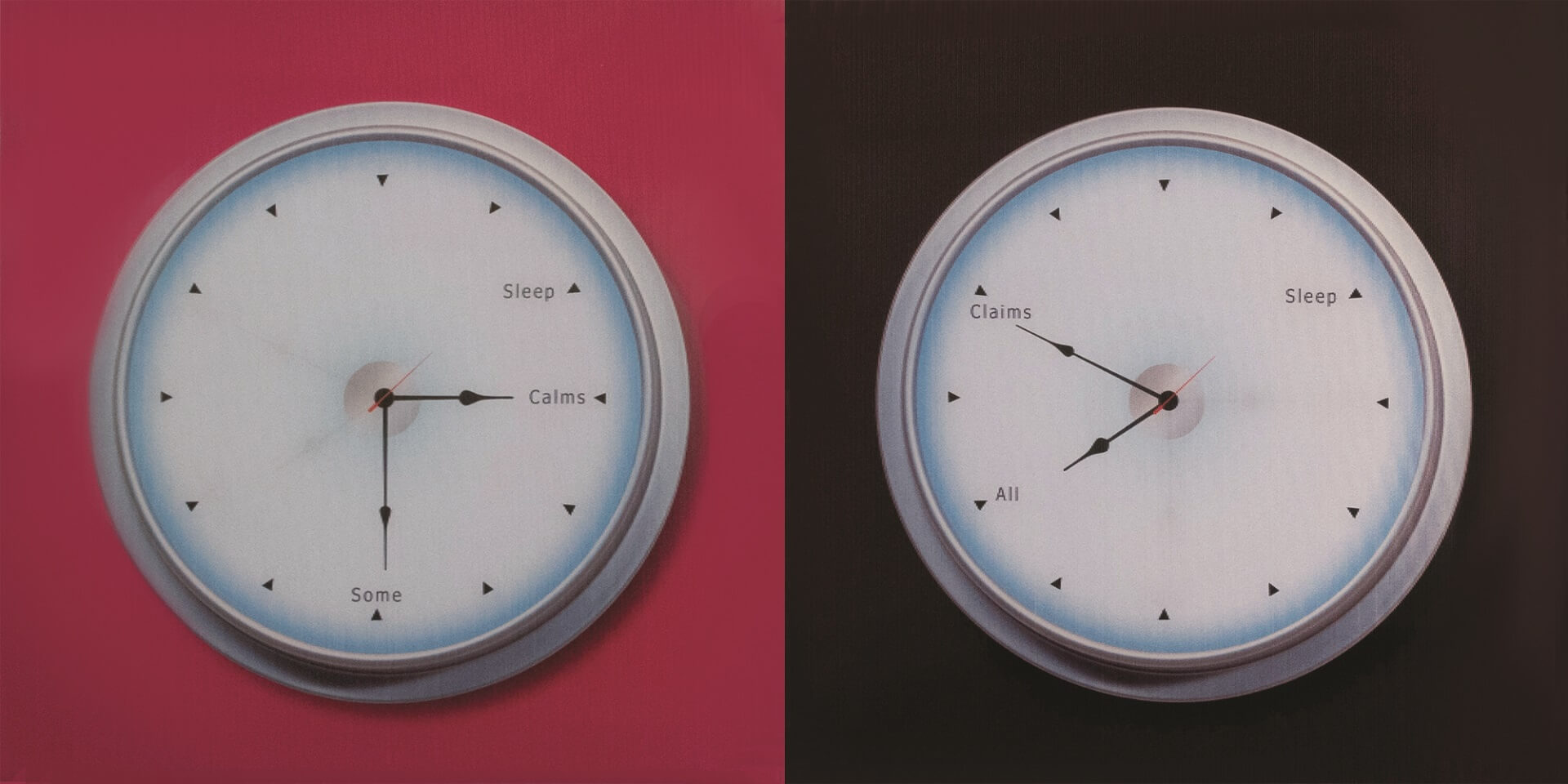

Raqs Media Collective, Sleep Clock, 2018

(Image Courtesy: Raqs Media Collective / Project 88)

Meanwhile, Monica Narula, Shuddhabrata Sengupta and Jeebesh Bagchi – through their Raqs Media Collective – presented the very important Sleep Clock to reflect on. “Sleep. Waking. Life. Death. The most intimate, singular as well as universal of experiences is rendered through a pair of clock-faces that mark the rhythm of every working day, and every life. The alteration between waking, working, sleeping on the one hand, and the beginning and end of life on the other hand, are the two sets of movements that stand behind the conception of this piece.”

Sandeep Mukherjee, Tear – 5, 2014

(Image Courtesy: Sandeep Mukherjee / Project 88)

And finally, in his Tear paintings, Los Angeles-based Sandeep Mukherjee overlapped various textures by repeatedly applying coats of paint to mask previous gestures. His paintings created disjointed layers of history, where past and present coalesced into a synchronous existence—much like the larger Indian narrative at the fair, which brought under the same roof (or sky!) artists with a common origin but very different journeys, perspectives, mediums and skills.

Text by Soumya Mukerji

With 12 years of writing and editing in the arts, culture, literature, social narratives, travel and lifestyle, Soumya has worked with The Times of India group, NDTV, Hindustan Times, Platform Magazine for the progressive arts, and contributed to The Guardian among others. When not at the desk, she travels, conducts college lectures and writes poems that sometimes find their way to interesting collaborations.